These moments come in short bursts and are quickly abandoned. The author focuses so much on questions about herself and her life, that she seems self-absorbed.

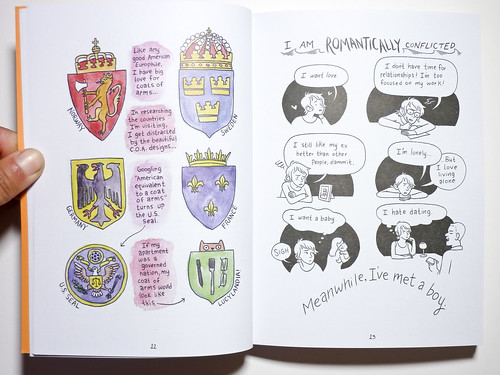

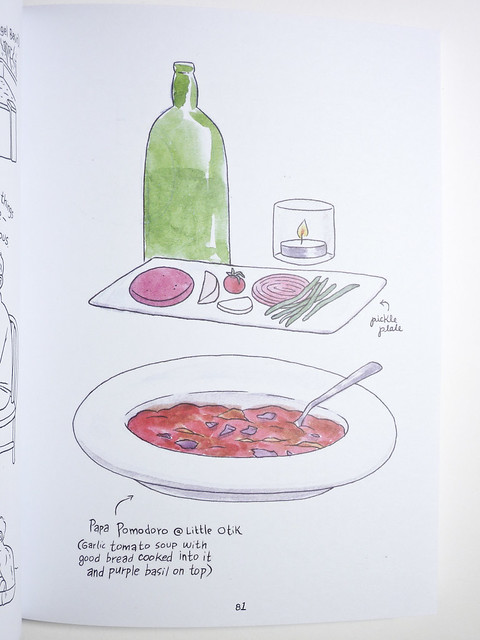

I can see why a book like An Age of License: A Travelogue might annoy some readers. Knowing these details about the author adds nothing to a conversation about culture, humanity, or travel. These details do not make a strong travelogue, especially when they take up a page or two, and the book was weak as a result. At another, she tells the readers that three fellow travelers drank all of her milk. At one point, Knisley points out her hair clip falls out while running for a train. The majority of the information in An Age of License is descriptions of what happened, where, with whom, and (sometimes) what they were eating. If Knisley were to use color to highlight aspects of her travel, the choice would make sense, but there appears to be no reason for which scenes are given more attention. For cohesion, she would have been better off sticking to one style and not suggesting to readers they were getting a partial deal. Knowing that she can draw and paint so well made me frustrated, as if she were too lazy or busy to care for the whole travelogue. However, every 5 pages or so, Knisley includes a page completed in water colors. Many graphic novels, including Persepolis and Maus, exist without color or sophisticated drawings. The images in Knisley’s book are simplistic line drawings, which is not surprising. Less obsession with making sure readers “get it” (even if there is nothing to “get”) would put emphasis on the important parts of the travelogue. This mostly seemed pointless, as it is not important to know who is moderating a panel nor who attended. In every picture at the con, she uses little arrows to point to people and write their first names. For instance, she’s invited to a comic con festival in Norway, which is the catalyst for her travels in Europe. Knisley seems a bit obsessed with readers knowing what everything in her work means. Gilbert appears to romanticize life while Dunham makes it seem impossibly difficult for young adults to get on. The story is described as “an Eat, Pray, Love for the Girls generation.” Neither of Elizabeth Gilbert’s book nor Lena Dunham’s show are really my style, to be honest.

Knisley, according to the back of the book, is known for her “food-focused autobiography,” so An Age of License possibly speaks to a different demographic.

I’d never heard of Lucy Knisley before, but because the graphic novel community is usually such a boys’ club, I picked up An Age of License to support a female graphic novelist.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)